It may not strike you as the most elegantly congruent and kindred of topics that a writer whose last project covered the 9,000 year history of beer is now having published a biography of Alexander Hamilton.

There is, however, one surprisingly deep and critical connection between the drink the world is most passionate about and the orphan bastard son of a whore no one has ever been able to shut up about since 2015.

How deep and how critical is the connection between Alexander Hamilton and beer? Believe it or not, the link arguably forms a crucial, load-bearing pylon upon which was erected the overarching principle of American constitutional law: judicial review.

Judicial review—what’s that again?

It’s nothing less than the power of the courts to determine if a law enacted by a legislative body, like Congress, is constitutional or not. If an act of Congress is found “repugnant” to the supreme law of the land, judicial review empowers judges to alter the law’s scope. Or even negate it all together. The hope, the goal is that, in the end, sacred political values remain untarnished by sometimes impulsive and wrongheaded politicians.

The judicial branch of our federal government (which includes, of course, the Supreme Court of the United States) has long exercised the authority of judicial review. By now, even though it is still controversial in fringey legal circles, centuries of precedent back it up.

But as you may very well know, judicial review is not a power that the U.S. Constitution explicitly delegates to anyone. The legitimacy of judicial review had to be established. It had to be argued for.

But as you may very well know, judicial review is not a power that the U.S. Constitution explicitly delegates to anyone. The legitimacy of judicial review had to be established. It had to be argued for.

You may recall hearing—after all, it’s one of those nearly universal school lessons to which bored and glossy-eyed high school students are made subject—that the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison was what established the practice of judicial review in the United States.

But this isn’t entirely true. Because even Marbury v. Madison was grown from a soil that includes earlier legal doctrine and a number of previous cases.

One of these previous cases? Yep. It involves Alexander Hamilton and beer.

But first! Did Alexander Hamilton actually drink beer? Did he love it? Should we place him anywhere near Samuel Adams in the constellational firmament of Founding Fathers whose preferred quaff was the delectable fruit of barley and hops?

I’m sorry, but the answer is short and unexciting: we don’t really know. Hamilton probably drank some beer, some time. He probably didn’t love it.

Our first Treasury Secretary and first love-him-or-hate-him powerplayer in national politics grew up in the tropics of the Caribbean. Mostly on the island of St. Croix. In the days before refrigeration and air conditioning were invented, it was difficult if not impossible both to brew beer and store it for any length of time in a hot, humid climate. Beer and wort (the sweet liquid obtained from malted barley that yeast is allowed to ferment) spoil too quickly in the tropics. And even in the summer months in northern climes. For most, beer used to be an entirely seasonal delight.

We do know from Hamilton’s tender years as a merchant firm clerk that beer was brought down to St. Croix. Such beer was probably brewed in New York or Philadelphia, and sold around Fredericksted and Christiansted, the island’s principal towns.

But in Hamilton’s time beer, ale, and porter would probably have been available only at a high premium on the sweaty, pestilential island of sugar plantations then under the flag of Denmark and Norway. It’s unlikely to have been the sort of drink that a poor adolescent clerk would have been able to get his mitts on much.

If the young Hamilton developed a taste for any alcohol at all it was probably the then-popular Madeira wine. Madeira hailed from the namesake Portugal-controlled archipelago some hundreds of miles off the coast of west Africa.

Drinkers in Spain and France were both snobbishly partisan about their local wines. Their governments were fiercely economically protective over them too, and allowed imports into their territories at a high price—when they were not banning it entirely. So Madeira was shipped by the cargo hold-full to America (and the West Indies or Caribbean). There to the likes of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson it was the thing to drink and offer to guests.

In all of Hamilton’s prodigious writings there are few mentions of beer. Even when it comes to other alcoholic beverages, nowhere does he ever favor drink or drinking with any poetic or nostalgic flourishes. (I think anyone who has thumbed through the Reynolds Pamphlet knows where Hamilton’s real vices lied. Booze, they weren’t.)

In all of Hamilton’s prodigious writings there are few mentions of beer. Even when it comes to other alcoholic beverages, nowhere does he ever favor drink or drinking with any poetic or nostalgic flourishes. (I think anyone who has thumbed through the Reynolds Pamphlet knows where Hamilton’s real vices lied. Booze, they weren’t.)

This isn’t to say the man didn’t apparently enjoy being in his cups now and then. Some have speculated Hamilton couldn’t hold his drink. This based on what his major frenemy, John Adams, remembered about Hamilton a year and a half or so after his death.

Adams burningly dismissed Hamilton as an “insolent Coxcomb, who rarely dined in good Company where there was good wine, without getting silly, and vapouring about his Administration, like a young Girl about her brilliants and trinketts.”

If Hamilton himself didn’t have any particular ardor for beer—we can safely speculate that he would have had it now and then, although it never would have been his first choice of a tipple—he was savvy enough to know that many of his countrymen went for it.

At one point Hamilton was girding up for the political hard-sell of imposing a tax on distilled spirits. (This was precisely what sparked the nowadays fondly remembered “Whiskey Rebellion” in backwoods Pennsylvania and elsewhere. It also made Hamilton plenty of new enemies in sundry other corners of the young nation, especially the South).

In the midst of advocating this contentious liquor tax, Hamilton instructed beer drinkers, homebrewers, and small-time entrepreneurs of the day to look on the bright side. Expensive booze, as he spinned it, would just make beer more popular and profitable!

Hamilton wrote in his first draft of his 1790 Report on Manufactures:

“The duties on ardent spirits may serve as a virtual bounty on beer, ale and porter and the impost on foreign spirituous liquors, encouragement to those made at home.”

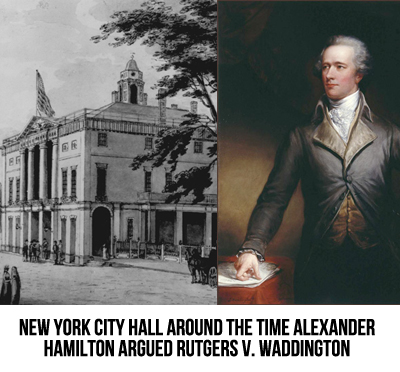

But it is really in his post-Revolution, pre-Treasury Secretary role as a lawyer in the shaky, struggling, depopulated, and half-burned-to-the-ground New York City that Hamilton, in a case related to beer and brewing, scored that aforementioned important win for the concept of judicial review.

Even though there was no love lost between Hamilton and John Adams, in this scenario it was almost as if Hamilton was taking a page from his rival’s playbook.

Adams had defended the Redcoat “lobsterbacks” who had shot up a snowball-throwing crowd in 1770, thereby committing what today Americans remember as the Boston Massacre. And fourteen years later, Alexander Hamilton decided to defended his own small party of offenders whom liberty-loving Yankees found odious and detestable.

Hamilton’s legal clients were not British soldiers. Possibly even worse, they were American loyalists. Tories.

It must be added here that in 1784 the Tories had lost. They were shamed, hated, exploited, and impugned at every turn. By being their legal counsel, Hamilton was really setting himself up to face one holy hell of a hullabaloo.

What was the crime of these Tory clients of Hamilton’s?

Well, it just so happened that, during the Revolutionary War, they had commandeered this nice, little, old patriot lady’s brewery. And all while gold-hearted farm boys from Virginia and Connecticut were being mowed down by musketfire, these Tories had been hard at work satisfying the thirsts of the Manhattan-occupying Redcoats and Hessians—the hated German peasant-mercenaries whose lord and princes in mainland Europe had been paid by their distant cousin George III to help slaughter American “rebels.”

Some quick background.

Remember, New York fell to the British in September, 1776. Hamilton—then a captain in a New York State artillery regiment—was on hand to breathlessly evacuate with the rest of the good guys. The foreign invaders sent George Washington and the whole gang packing in a panic to Harlem, then White Plains, until finally the Americans had had their hind ends kicked all the way to Bucks County, PA. The Redcoats were left squeegeeing off the scales of all the “Don’t Tread on Me” snakes they had been treading on for months.

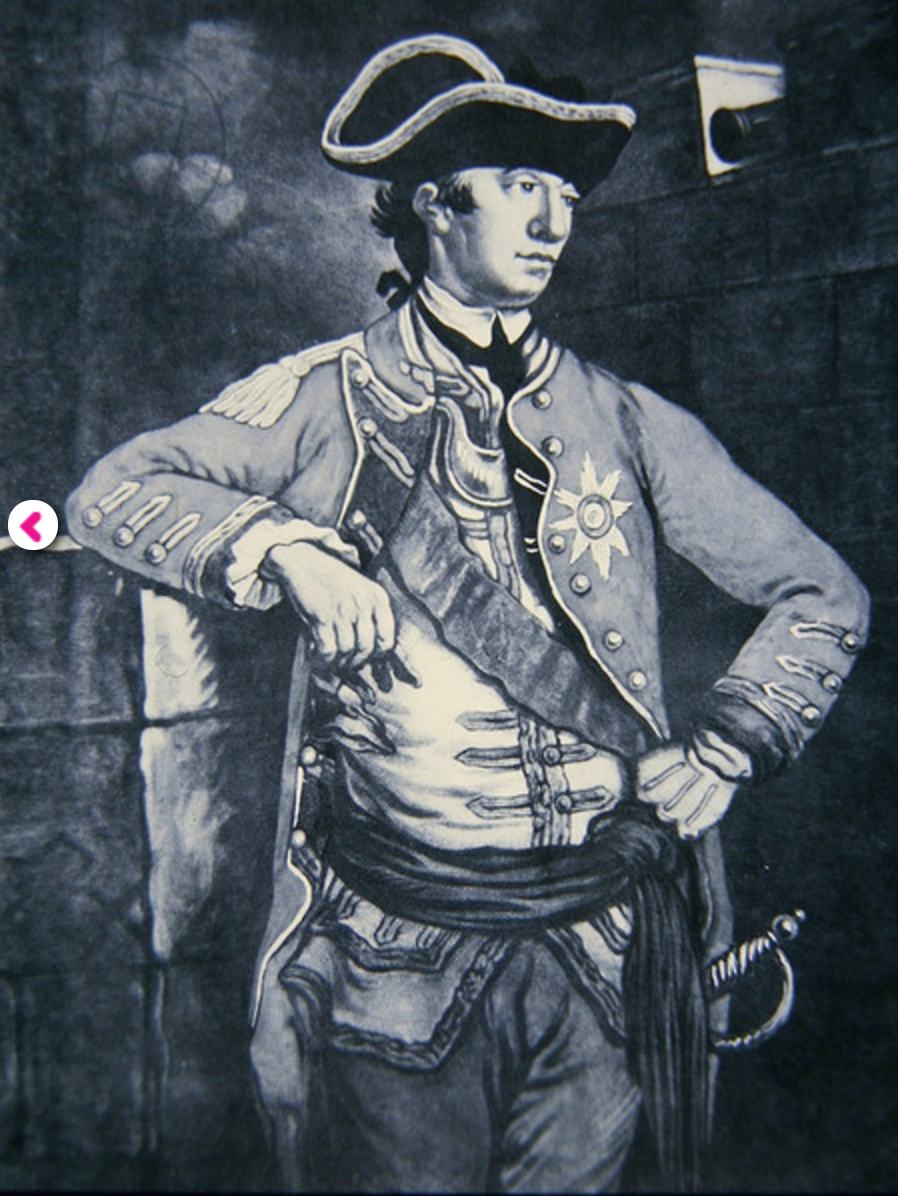

Moving right into the prize city to which he and his countrymen had just so successfully laid siege, His Majesty’s Major General Sir William Howe turned to the task of keeping his troops fed, supplied, and victualed.

That meant procuring people who could procure beer.

And who better to do that than some of New York’s thousands and thousands of homegrown Tories? (New York, Long Island, and Westchester County were, in the 1770s and 1780s, dominated by Union Jack-waving loyalists).

The Tories had the skill set. They had the lay of the land. But what they didn’t have? A brewery.

However—guess who did have a brewery? And a malthouse too, come to think of it?

Friendly old freedom-loving widow Elizabeth Rutgers. That’s who.

When the Redcoats came knocking, the widow Rutgers had flown the coop. She fled Manhattan along with the most of the rest of the American patriots. The ones who were lucky enough not to get taken prisoner, anyway.

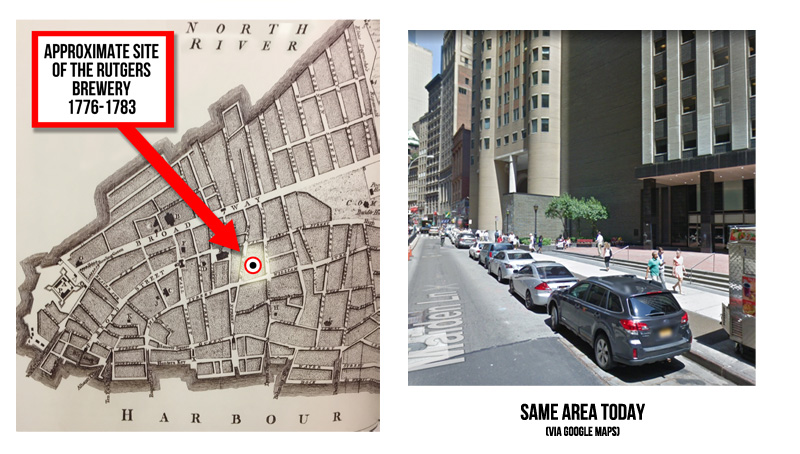

The British authorities, including Commissary-General Daniel Wier, were keen to get some proper libations going for their victorious forces. Ultimately they took over three New York City breweries. Mrs. Rutger’s property was seized. Her brewery and malthouse were placed in the hands of Loyalist merchants by the names of Benjamin Waddington and Evelyn Pierrepont. (And just to help paint the mental picture, this is the “dude” form of “Evelyn.” You know, like Evelyn Waugh.)

The British authorities, including Commissary-General Daniel Wier, were keen to get some proper libations going for their victorious forces. Ultimately they took over three New York City breweries. Mrs. Rutger’s property was seized. Her brewery and malthouse were placed in the hands of Loyalist merchants by the names of Benjamin Waddington and Evelyn Pierrepont. (And just to help paint the mental picture, this is the “dude” form of “Evelyn.” You know, like Evelyn Waugh.)

Before we get too sentimental about old widow Rutgers and how tasty and fortifying her patriotically virtuous and locally produced craft offerings must have been, though, take note. The Rutgers brewery was in a “shambles” (as court documents put it) when she abandoned it in 1776.

If we’re being honest, Mrs. Rutgers probably churned out brews that were passable, nothing more. And there’s no reason to believe that she was the actual in-house brewer. It’s more likely she just owned of the property—which she had inherited from her late husband, to boot.

In another snaggy setback to any knee-jerk patriotic assumptions we might have, it was the new sheriffs in town—Waddington and Pierrepont—who took the pains and spent the money to seriously class up the joint.

Waddington and Pierrepont imported a new brew kettle. They rebuilt the boiler and added a storage area for firewood. You might say the Tories brought the place kicking and screaming into the 18th Century. In fact, Waddington would later prove in court that he had had to invest 700 pounds just to get the brewery capable of brewing again.

Waddington and Pierrepont operated the place through all the ups and downs of the war. And it should be said that in New York, those ups and downs were mostly ups. Even though George Washington remained ever champing at the bit to storm Manhattan, the enemy stronghold it had besmirched his honor and reputation to have lost in the first place, and put it back in the American column, no opportunity to take a swipe at this ever came his way.

In New York, the powdered wig “God Save the King”-belters were large and in charge all through the rest of the war. (This didn’t entirely work to their advantage, because the historical men’s haberdasher Hercules Mulligan—who in the rush to evacuate in 1776 had been taken prisoner by the Redcoats—really does seem to have used his position to get loose-lipped British officers to spill military secrets while he was taking their measurements for new uniforms and such. Not that his role isn’t exaggerated in Hamilton the musical. It is. But—it seems Mulligan was such an effective spy that George Washington himself called on him for breakfast upon victoriously reentering the city in 1783.)

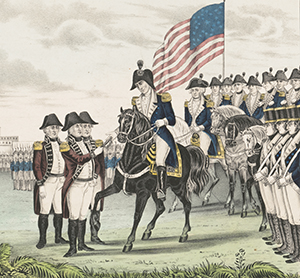

Finally came the Battle of Yorktown. The lived experience of this back in 1781 wasn’t quite as decisive and picturesque as, say, VE-Day. There were no lively scenes of Joseph Plumb Martin publicly necking with Molly Pitcher in Times Square or anything like that. But Yorktown did break the back of the British people’s willingness to keep fighting and funding the war. Effectively it was the beginning of the end.

Finally came the Battle of Yorktown. The lived experience of this back in 1781 wasn’t quite as decisive and picturesque as, say, VE-Day. There were no lively scenes of Joseph Plumb Martin publicly necking with Molly Pitcher in Times Square or anything like that. But Yorktown did break the back of the British people’s willingness to keep fighting and funding the war. Effectively it was the beginning of the end.

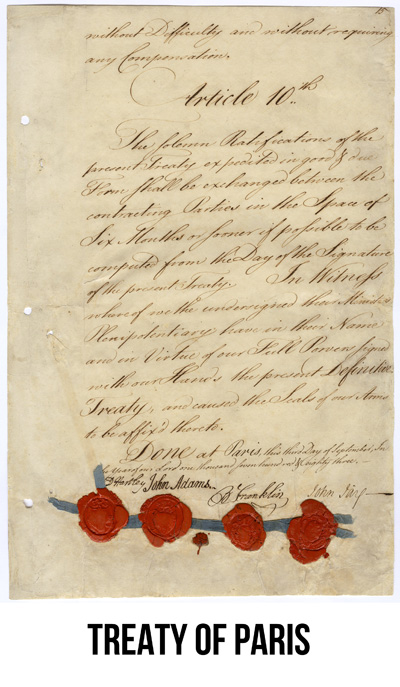

The belligerent parties, the United States and Great Britain, negotiated the Treaty of Paris—which officially halted the hostilities in 1783. This document impinged directly on the destiny of New York. It was laid out that the Redcoats would soon be forced to pack up their kits and sail off to Bermuda, Nova Scotia, or all the way back across the Atlantic.

As the war wound down, all soon realized the inevitable: all the American property seized by the British was going to have to be returned to its rightful owners. Even before Evacuation Day, fork-tongued traitor-brewers Waddington and Pierrepont were obliged to start paying rent to Elizabeth Rutgers through her son, Anthony.

But Anthony wasn’t satisified. (Cue the soundtrack: “He can never be satisfied!”)

Mom and son didn’t just want to collect current rent until Evacuation Day. The Rutgers demanded back rent too. In fact, they wanted payback for the entire span of time Waddington and Pierrepont had been stinking up the place.

Then, just a few days before Evacuation Day, Mrs. Rutgers’ brewery burned to a cinder.

Was this an accident? A prank? A devastating scorched earth policy? No one seems to have been able to prove any wrongdoing then or now. If there are cold case files for New York City Fire Department’s arson investigators, perhaps this could be added to the granddaddy of them all: the mysterious 1776 fire that leveled a third of the city.

Anthony and Elizabeth Rutgers were not happy. So in February 1784, widow Rutgers filed in the Mayor’s Court of New York City. She was going to sue Waddington for 8,000 pounds.

Hamilton signed on as counsel in the lawsuit. But not to help Elizabeth Rutgers get her money back, no.

Instead Hamilton took the case to defend Benjamin Waddington.

Hamilton planned to argue that Waddington’s use of the Rutgers brewery was legal, and that he didn’t owe the brewery’s owners squat. How did Hamilton justify this? The “laws of war.” Enemies almost always seized property abandoned by the other side.

Hamilton was going to push even further, in fact. He planned to help the Tory brewer recover his losses—from all the improvements he had made to the Rutgers’ shambles of a brewery as it stood in 1776.

On its face, Rutgers v. Waddington wasn’t anything special. It was only one of hundreds upon hundreds of similar cases that had come to bog down New York courts in the aftermath of British occupation.

On the other side of Evacuation Day, Americans started trickling in real numbers back to New York City. This included Hamilton, who moved down from Albany after completing the equivalent of a get-to-be-a-lawyer-quick course. (It also included Aaron Burr, eventual vice president of the United States and murderer of Hamilton, who had already set up shop a few blocks away from Hamilton’s practice.)

Most of the returning patriots were hungry for revenge against loyalists one and all. And the returning patriots weren’t about to listen to anyone try to sweet talk them into waiting until the dish was cold.

Revenge could also be as formal as new laws. The state legislature of New York had enacted a number of punitive measures to make the Tories pay for their aiding and abetting the enemy. This included the 1779 Confiscation Act, which authorized state authorities to condemn, seize, and auction off the entire estates of New Yorkers who had “adhered to the enemy.”

The 1782 Citation Act voided debts that patriots owed to Tories.

And finally the 1783 Trespass Act officially made loyalists financially liable for patriot property they had used during the occupation by the British.

The goal here wasn’t strictly punitive. It was to effect a redistribution of wealth on a massive scale.

The goal here wasn’t strictly punitive. It was to effect a redistribution of wealth on a massive scale.

Tories, after all, had been most of the pillars of the Manhattan’s community: the big doctors, merchants, lawyers, and so on. (Interestingly enough, this did not include bankers! New York City didn’t have a single bank until that same year, 1784, when Hamilton helped some partners hang the shingle for the Bank of New York.)

It was Tories who owned the biggest plots of land, the finest houses, the fattest livestock, the flashiest furnishings. And why, many Americans wanted to know, after being on the wrong side of the war, should the traitors get all their good stuff back? Why should the social advantages they enjoyed before the war be upheld after it, too?

The patriotic minority of New Yorkers were not-so-quietly conspiring to make all this Tory property up for grabs. The wise, detached, all-seeing statesmen crafting legislation up in Albany were in a fine fiddle to help them do just that.

Alexander Hamilton was decisively opposed to all the anti-Tory mania that fueled the Trespass, Citation, and Confiscation Acts.

If it were up to Hamilton, everyone in town would have just gotten over it and moved on. Hamilton believed that the wealthy Tories should see their real estate portfolios returned and their wealth untouched. What he wanted more than anything else was to get everyone to simply move on with the business of rebuilding a world-class seaport and commercial municipality.

It truly hit Hamilton where it hurt—his ego—when, en masse, Tory gentlemen and ladies began skipping town. They were emigrating away from the United States to seek greener pastures in England or Canada. Hamilton didn’t want to be a big fish in a small pond of thieving rubes. He wanted to be a peer among gentlemen, in a place where the economy was humming.

But even Benjamin Waddington up and left, leaving Hamilton to represent him through his son and business agent, Joshua Waddington.

“Our state will feel for twenty years at least, the effects of the popular phrenzy,” Hamilton wrote.

And here was the thing. The United States Congress was on Hamilton’s side.

Recall that the Treaty of Paris had been negotiated by Congress. (Keep in mind this was before the U.S. Constitution was even drafted, so there was no president, no House of Representatives, no Senate—just a unitary legislative body to coordinate a “league of friendship” among the states). And a key provision of the treaty had been clear and explicit about how the American loyalists were supposed to be dealt with.

Recall that the Treaty of Paris had been negotiated by Congress. (Keep in mind this was before the U.S. Constitution was even drafted, so there was no president, no House of Representatives, no Senate—just a unitary legislative body to coordinate a “league of friendship” among the states). And a key provision of the treaty had been clear and explicit about how the American loyalists were supposed to be dealt with.

According to the Treaty of Paris, the Tories were to be unmolested in their persons! The Tories’ rightful property was to be secure! The debts owed to them were to be honored!

So here was the reality: Congress had made one law. The State of New York had turned around utterly contradicted it with its own legislation.

As public policies, the Treaty of Paris on the one hand and the Trespass/Citation/Confiscation Acts on the other were diametrically opposed. That left everyone hanging with the question: which one was to be upheld? Which one was the “real” law, Congress’s or New York’s? Which was the “higher” law that should actually have legitimate force behind it?

Here is where we see how strange and anachronistic the legal values we share today would be compared to those of an extensive class of Revolutionary Era patriots in the 1700s.

The standard on which so many of the Founding Generation operated was the standard of “legislative supremacy.”

Legislative supremacy was largely the position of politicians like Alexander Hamilton’s rivals Melancton Smith, Marinus Willett, and George Clinton. They, in essence, believed that if the representatives of the sovereign people of New York State passed a law, no court could undo it.

A law written by the legislature and approved by the governor in Albany may have flown in the face of any higher legal principle or precedent. But it was still a law. And if it was a law, then the People had spoken. No unelected judge could do a thing to change it.

To put it another way, “tyranny of the majority” ruled the day. There were no rights, repeal, or recourse for minorities, like the Tories.

Hamilton was fiercely, vituperatively an opponent of this whole legal understanding.

To Hamilton, the Trespass Act and so on—the laws which were enabling the wholesale downwards redistribution of wealth—were even more evidence of what he had observed all along during the war and in its wake: that the state governments were reckless and irresponsible.

Hamilton was ardent in his conviction that too much pure democracy placed power in the hands of money-grubbing hucksters: low-class Have Nots who would only take from the Haves. That such people also almost always proved incompetent with the job of actually administering a government? That only made things worse.

Hamilton yearned for Congress to be anointed power center that could overrule the states. Whip them into shape. Make them to carry through on their responsibilities. Force them to behave like honorable nations do.

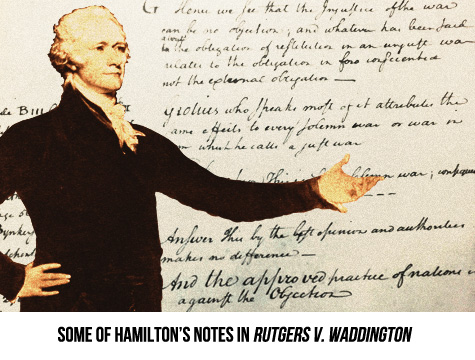

Rutgers v. Waddington was therefore, to Hamilton, much more than a case about back rent on a burned-down brewery.

It was a case in which he could throw down a gauntlet over sweeping, all-encompassing, world-historical legal issues.

Rutgers v. Waddington was Hamilton’s chance to argue that Congress, through the Treaty of Paris, was capable of enacting a law superior to the acts of a State legislature. (In certain spheres, anyway, like diplomacy and international affairs).

Hamilton was also in effect declaring that the courtroom—the domain of lawyers and judges—was the proper place to determine which law should carry force: Congress’s, or the state’s.

Hamilton argued the case in late June of 1784 before Mayor James Duane and five aldermen. Representing the plaintiffs, the Rutgers, was attorney general Egbert Benson. Two of Hamilton’s own good friends, Robert Troup (a very close pal never mentioned in the musical) and John Lawrence (not to be confused with John Laurens) were also on as co-counsel for Rutgers.

The 29 year-old Hamilton caused a scandal, a sensation, by defending Loyalists in court. The New York Journal newspaper even published a poem castigating him in the manner of a perilous Roman general, and raking Hamilton over the coals for putting his career as an attorney ahead of all his patriotic acts in the lead-up to the war.

Wilt thou Lysander, on this well earn’d height,

Forget thy merits and thy thirst of same;

Descend to learn of Law, her arts and slight,

And for a jobb [sic] to damn your honor’d name!

The issues which were so thorny then are not thorny now.

Motivated exactly by the clutch of jurisdictional clashes that came about during and after the war, the United States Constitution includes the “Supremacy Clause.” The Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Clause 2) codifies that, within its proper areas of operation, federal law always trumps state law. The governing document of 1784, the Articles of Confederation, lacked such a clause—along with its many other demonstrably disastrous shortcomings. (Hamilton called the Articles of Confederation “unfit for either war or peace.”)

Mayor James Duane (who in his position as mayor was also judge in the case) was apoplectic over Rutgers v. Waddington. In his arguments, Hamilton indeed made a compelling case. But for Mayor Duane to decide in favor of Waddington? That would be politically untenable.

Mayor James Duane (who in his position as mayor was also judge in the case) was apoplectic over Rutgers v. Waddington. In his arguments, Hamilton indeed made a compelling case. But for Mayor Duane to decide in favor of Waddington? That would be politically untenable.

Duane’s actual decision in the case is a chore to parse. This is most likely because Duane had to reserve something for the patriot—that is, Elizabeth Rutgers’—side, or face ruin both with his personal reputation and at the ballot box next election.

When damages were awarded (here a jury got to consider the facts of the case, which they did, possibly over beers, at a place called Simmons Tavern near City Hall) 791 pounds were to go to the Rutgers.

This was far, far less than the 8,000 they had sought. So in that it was a partial victory for Hamilton.

But here was Hamilton’s real victory. Duane had to concede that in a civilized nation, a local legislature simply cannot have the power to strike down the acts of a national body, like Congress, with power over war and peace. After all, the power to make peace must include the power to make, and enforce, peace treaties.

The public outcry against Hamilton and Duane, for partially setting aside the act of the state government, was intense. Yet Hamilton, who later described the case as a “compromise” and “partial success” had significantly furthered his intellectual project of making a case for a strong central government. This scheme would, of course, include judicial review, which Hamilton would advocate further in The Federalist #78 and elsewhere.

George Washington had been keeping tabs on this case from afar. He did not approve of New York’s violations of the Treaty of Paris—which he said would “destroy our National character—& render us as contemptable [sic] in the eyes of Europe as we have it in our power to be respectable.”

As for how Hamilton had helped steer the case, and given a badly needed jolt of legal legitimacy to Congress, Washington wrote “reason seems very much in favor of the opinion given by the Court, and my judgment yields a hearty assent to it.”

A United States of America without judicial review would be unrecognizable. For generation upon generation the principle has stood to remind us that there is fundamentally more to civilization, more to the the rule of law, than acts of a majority of the people.

Judicial review has decided cases in favor of both rich and poor, powerful and powerless, liberal and conservative. It’s hardly as if judges and lawyers decide every case in the favor of true justice. But the system we have is worlds better than one in which every issue would be left to the majority—with individual rights and the security of property subject to the weathervane whim of elected politicians.

Judicial review is like the Constitution. In Hamilton’s words, it “may not be perfect in every part, is, upon the whole, a good one; …such an one as promises every species of security which a reasonable people can desire.”

POSTSCRIPT:

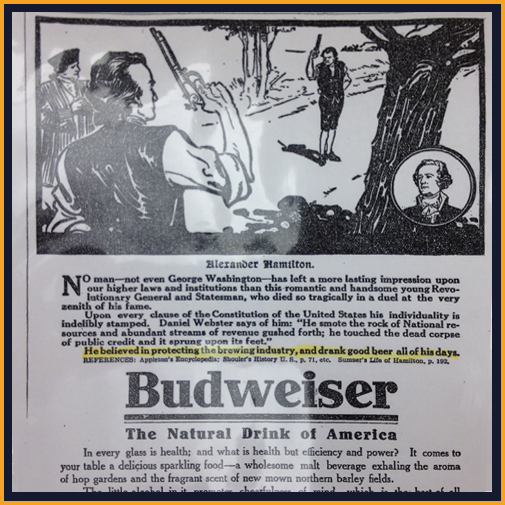

This.