A short piece I wrote for The Washington Post

this weekend concurs with the decision of the

City Council of Charlottesville, Virginia, on Monday, February 6, to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from a prominent public city park in that city.

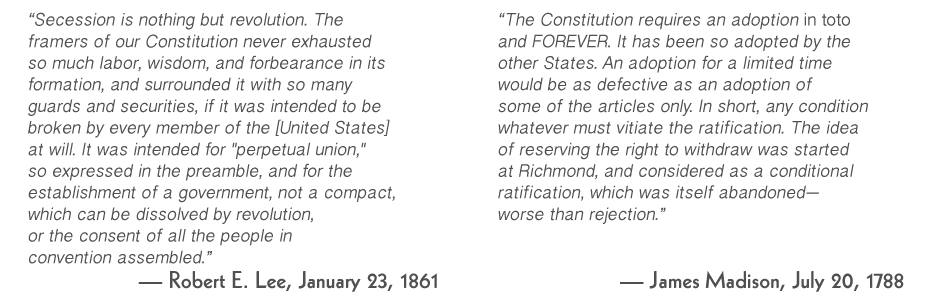

I believe this was the right thing for the duly-elected local representatives of the people of Charlottesville to do. However, my argument does not so much stand on the basis of Lee as a defender of the vile institution of slavery. It is true that Lee was not at all an outspoken proponent of human bondage. But as eventual General-In-Chief of the armies of the Confederate States, the fact that his personal attachments to slavery were only mild certainly damns him with faint praise.

(Lee inherited about 70 slaves from his father-in-law when that man died in 1857. The venerated Confederate general abided by the wishes of his wife’s father when he manumitted, or legally freed them, in accordance to the will of George Washington Custis, which stipulated they were to remain in service for five more years. Before that time came, however, Lee in 1859 ordered three runaway slaves severely beaten, sending for a local constable to do the job when one of his own plantation overseers refused to, and standing by close at hand to ensure maximal pain was inflicted. Later, when the Civil War broke out, Lee sent other slaves in his charge to toil further within the Confederate interior to discourage them from seeking their freedom behind Union lines.)

Instead, my argument for removal the statue (or alternatively radically altering its presentation) is that Lee is undeserving because he committed the act of treason against the United States.

Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution states that “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” And Lee’s actions from 1861-1865 are prima facie evidence that he undertook just this. His commission of the crime is valid despite the fact that the Lincoln Administration and subsequent postwar authorities chose never to put Lee on trial for treason.

Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution states that “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” And Lee’s actions from 1861-1865 are prima facie evidence that he undertook just this. His commission of the crime is valid despite the fact that the Lincoln Administration and subsequent postwar authorities chose never to put Lee on trial for treason.

The prosecutorial forbearance was by design. In the wake of the war most officers of the federal government were chiefly concerned with rebuilding and reuniting the war-torn country, not persecuting and making grisly examples of secession’s perpetrators and the legions who followed them.

Only a single Confederate officer, Captain Henry Wirz, was ever convicted and executed for war crimes. And even the treason trial of Confederate President Jefferson Davis was abandoned before a sentence was ever issued. Even Aaron Burr, whose putative attempts to provoke disunion were trifling in comparison, had to sit through a whole trial.

Treason is not a charge to be thrown around lightly. In fact, the Founding Fathers were acutely sensitive to the term’s flagrant and damaging abuse under the monarchy of Great Britain, where one could brutally drawn and quartered for, for example, being Catholic, trespassing on royal hunting grounds, or forging counterfeit shillings. The Founders were so adamant that treason be as narrowly defined as possible in the republic they were constructing that it is the only criminal charge spelled out in the Constitution, the Supreme Law of the Land.

And as I seek to point out in the piece, no one need cling to a cravenly legalistic, morally blind, paper definition of treason to rightly impugn Lee and the Confederacy, either.

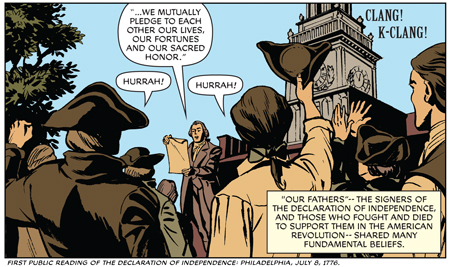

The United States of America would have no moral standing as an independent nation if rebellion was unjustifiable in all cases. There are circumstances that indeed make levying war against and adhering to the enemies of a country a moral imperative. The American Revolution, in which colonists wholly unrepresented in their government stood up to the forces of King George III and colluded militarily with Britain’s enemy, King Louis XVI of France, continues to stand as a defining example. To briefly recap what I set out in the Post, the set of circumstances that gave rise to the Civil War were worlds away from those of the American Revolution because the Southern states had enjoyed not only fair but excessive, preferential representation in the U.S. government.

The United States of America would have no moral standing as an independent nation if rebellion was unjustifiable in all cases. There are circumstances that indeed make levying war against and adhering to the enemies of a country a moral imperative. The American Revolution, in which colonists wholly unrepresented in their government stood up to the forces of King George III and colluded militarily with Britain’s enemy, King Louis XVI of France, continues to stand as a defining example. To briefly recap what I set out in the Post, the set of circumstances that gave rise to the Civil War were worlds away from those of the American Revolution because the Southern states had enjoyed not only fair but excessive, preferential representation in the U.S. government.

In the State of Virginia’s own convention in which the Constitution was ratified, the delegates made plain that if the federal government “perverted” its powers to cause the state “injury” or “oppression,” it would consider the sovereignty of its people infringed and the state’s attachment to the union rendered null. However, I have yet to be persuaded how the undisputedly fair election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860—the development that set off the first wave of secession in the South—arose to a “perversion” of the Constitution.

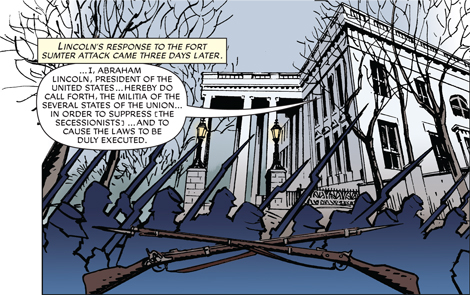

The federal government was furthermore acting under its constitutionally delegated powers under Article I, Section 8 to call forth the Virginia militia to aid it to “suppress insurrections and repel invasions” (which, by virtue of the Militia Act of 1795, Congress legislatively delegated to the Executive Branch and never bothered to take back).

And it is this latter act that has gone down in history as what compelled Virginia—after an initial overwhelming vote in February, 1861 to remain with the Union—to secede. Robert E. Lee, after soul searching, went along with his home state.

And it is this latter act that has gone down in history as what compelled Virginia—after an initial overwhelming vote in February, 1861 to remain with the Union—to secede. Robert E. Lee, after soul searching, went along with his home state.

So the secessionists in the “cotton states” had nothing close to justifiably revolutionary grounds. Virginia had played a fundamental role in writing the rules of the American republic. And she had seen to it that those rules would be tweaked in her favor (including Thomas Jefferson’s behind-closed-doors angling to get the seat of government on the Potomac rather than in Philadelphia or Baltimore as others had proposed). Yet when a single election did not go their way, they could not abide remaining in the Union. And most Virginians ultimately could not abide siding against them. Not even when a last-minute “unamendable amendment” that would forever negate the federal government’s ability to disestablish slavery in the states it existed was offered.

Lee, so exalted as a man of honor, broke the oath he had taken in 1829 to bear true allegiance to the United States of America and obey the orders of the commander-in-chief of its military. This vow he freely swore at the culmination of his education (paid for in full by by the taxpayers of the United States, South and North) at West Point, where as a young man he graduated 2nd in his class. Lee turned his back on some of his own most dearly-held beliefs. All the more reason to think twice about the value of states and municipalities endorsing him with public statuary.

Let’s face it. Statues like the one in Charlottesville don’t exist as simple reminders of history. They embody a very particular message.

Let’s face it. Statues like the one in Charlottesville don’t exist as simple reminders of history. They embody a very particular message.

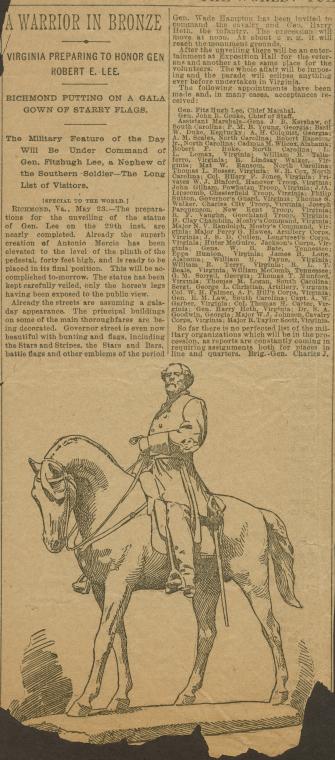

Lost on many contemporary viewers is the historical significance of what kind of statue this is. To sculptors throughout the centuries, horses have been artistically challenging and expensive subjects to render. Few if any American artists had the wherewithal to produce them, and indeed even Charlottesville’s Lee statue had to be produced by an Italian immigrant. Equestrian statues have long been reserved for conquerors and symbols of militarism. Lee as a mounted horseman here carries a special, glorifying significance, designed not to invite critical engagement with the man and the legacy but to immortalize him as a gallant warrior—a “cavalier” as proponents of the Lost Cause like to say.

On the day Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee statue was presented to the public in 1924, it was draped in Confederate battle flags and attended by singing, all-white schoolchildren—who themselves were staged and dressed to present as a “living” Confederate flag.

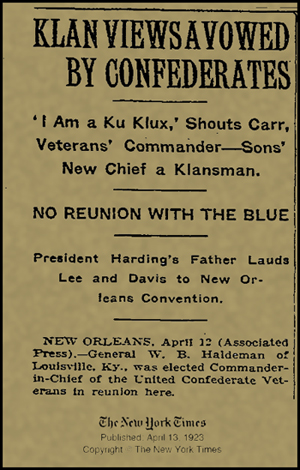

Groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Daughters of the Confederacy had planned and presided over the ceremony. The reigning head of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was a Virginia fish and game official named W. McDonald Lee. During his recent reelection as “Commander-In-Chief” that organization, the convention thronged with attendees confirming they were members of the Ku Klux Klan. Reports in many contemporary newspapers suggest Mr. Lee himself was a Klansman. And Julian S. Carr, the Commander in Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, was an open and avowedly a member of the white supremacist terrorists.

Charlottesville’s Lee statue was not intended to chronicle the history of the Confederacy. It was intended to perpetuate it. In spirit if not in practice. That is the message of the statue—and why it is absurd leave the statue to stand as is, or regard it as a mere innocent signpost of a past era.

It is distasteful but absolutely unsurprising that protestors (including a Republican gubernatorial candidate) have denounced the Charlottesville City Council for conspiring to “rewrite history” and besmirch the heritage of the Commonwealth. These pro-Lee activists have compared those who want the statue removed to the hateful swine of the Islamic State—notorious for vandalizing and destroying Middle Eastern archeological sites with religious symbols that predate Islam. The pro-Lee activists have demeaned the Charlottesville City Council members as fascists and tyrants executing the gravest acts of political correctness.

These protestors are as wrong as they are laughable in the extreme of their rhetoric. For to consider their position sound is to believe that perpetuating the spirit of the Confederacy is an acceptable thing for a 21st century municipality to publicly endorse.

These protestors are as wrong as they are laughable in the extreme of their rhetoric. For to consider their position sound is to believe that perpetuating the spirit of the Confederacy is an acceptable thing for a 21st century municipality to publicly endorse.

I cannot and would not speak for all those who want to see Confederate statues removed. In fact, I don’t doubt for a second that there are many among the ranks of the so-called “campus left” who would like to paper over American history and effectively make all evidence of the Confederacy disappear.

But my contention is the exact opposite.

Confederate history absolutely matters. We should never forget it.

And it’s because Confederate history matters that the statue should not stand as is.

In fact, Americans who choose to be involved in the political process and public affairs in any way should never stop thinking about Confederate history.

Because wrapped up in the history of the Civil War—and, yes, absolutely and unreservedly on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line— are all the evidences of our nation’s capacity to put economic issues ahead of human values; to distort, caricature, demonize, and exploit nonwhites; to place greed ahead of justice; to rush into warfare without a sober assessment of the suffering it will exact upon enemies and allies; to devolve into petty regionalism and ghettoization by ideology; and to demagogue and goad the vast and unprivileged majority into the service of the powerful few.

Because wrapped up in the history of the Civil War—and, yes, absolutely and unreservedly on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line— are all the evidences of our nation’s capacity to put economic issues ahead of human values; to distort, caricature, demonize, and exploit nonwhites; to place greed ahead of justice; to rush into warfare without a sober assessment of the suffering it will exact upon enemies and allies; to devolve into petty regionalism and ghettoization by ideology; and to demagogue and goad the vast and unprivileged majority into the service of the powerful few.

On the heels of his surrender at Appomattox, the Confederate general forbid his men to melt into the wilderness and sustain the fight through a prolonged campaign of guerilla warfare. Late in 1865, he humbly wrote Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant to request the restoration of his American citizenship. He signed an oath of allegiance to the United States. In the last years of his life, Lee quietly spent his energies reviving a small college in Virginia’s Great Valley. He chose to be buried in civilian clothes. These legendary acts of humility and contrition are, to my mind, singular examples we could all use some looking to in our political, professional, and personal lives. They leave the elder Lee ennobled and elevated.

That’s the kind of statue the public should see. And it’s the exact opposite of what the Charlottesville statue is.