Researching my latest project, lately I have been (psychically if not physically) spending quite a bit of time in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts—and contemplating how those cities should be drawn. This has been cause for me to reacquaint myself with a favorite illustrator, Barbara Westman.

Researching my latest project, lately I have been (psychically if not physically) spending quite a bit of time in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts—and contemplating how those cities should be drawn. This has been cause for me to reacquaint myself with a favorite illustrator, Barbara Westman.

My new book (the details of which I will announce soon), like The U.S. Constitution: A Graphic Adaptation, The Gettysburg Address: A Graphic Adaptation, and The Comic Book Story of Beer is also a nonfiction graphic novel. Its subject matter isn’t one immediately associated with the star urban centers upon the dirty water of the banks of the River Charles. But it turns out it really should be.

Nevertheless, the preparatory work for the manuscript has necessitated envisioning both Boston and Cambridge at many points across the 20th and present centuries. This proud and pleasant diversion into the state where I grew up (but regrettably have never lived as an adult) recently sent me scrambling to Alibris to acquire and in some cases re-acquire the collected works of one of my favorite illustrators, Barbara Westman.

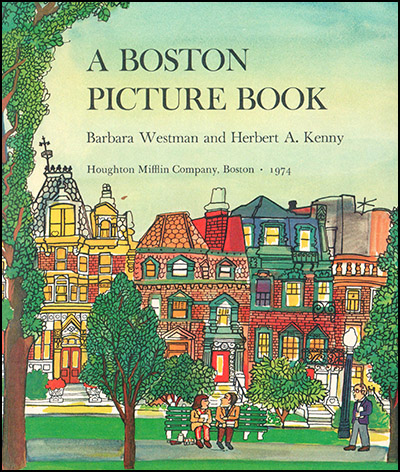

I first came across her work in my perfectly sufficient yet perfectly unremarkable elementary school’s perfectly sufficient yet perfectly unremarkable library. I have ever been a mediocre achiever when it comes to cross-referencing memories to years—they mesh with quite less than rack-to-pinion gearing efficiency in my head—but I would have to guess this was in 3rd or 4th grade. And that first impression-making collection was probably A Boston Picture Book, published in groovy old 1974.

It was a case of love at first sight. Because having been born and raised in its suburbs, Boston had undeniably come to serve as the Ur cityscape of my imagination and boyhood aesthetics. And over the course of an early lifetime that tracked with the slow and painful realization that I couldn’t really draw and would probably never be able to, Westman’s pen and ink and watercolor drawings somehow gave me a temporary palliative, candy-bar-and-Coca-Cola high and boost of confidence.

It was a case of love at first sight. Because having been born and raised in its suburbs, Boston had undeniably come to serve as the Ur cityscape of my imagination and boyhood aesthetics. And over the course of an early lifetime that tracked with the slow and painful realization that I couldn’t really draw and would probably never be able to, Westman’s pen and ink and watercolor drawings somehow gave me a temporary palliative, candy-bar-and-Coca-Cola high and boost of confidence.

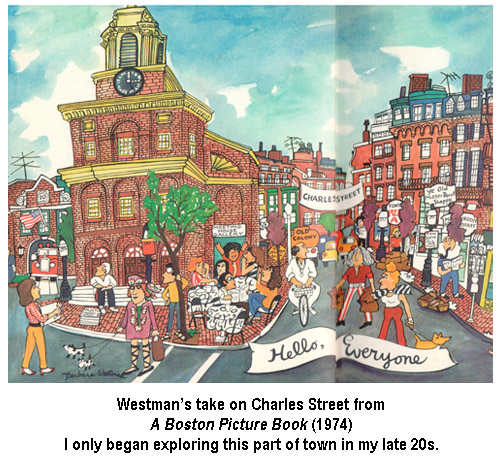

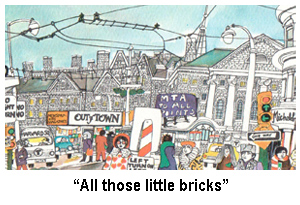

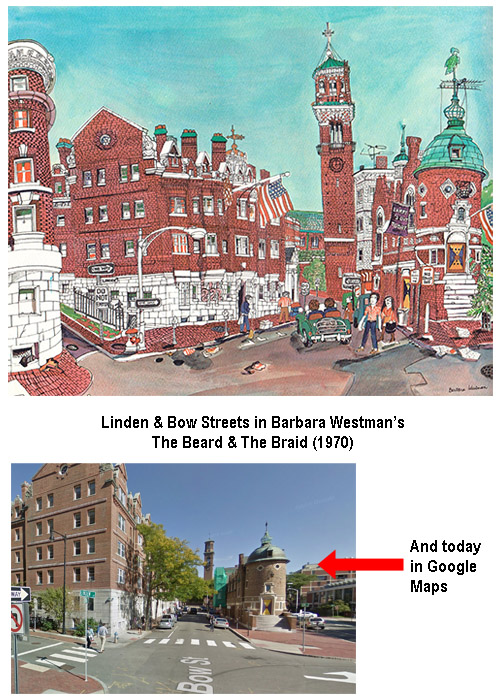

For here were drawings that seemed like something a hard-working kid might be able to pull off. In other words, at an age where I still essentially beheld photorealism as the homing beacon to which all artistic endeavor must naturally slog, Westman’s depictions of Boston neighborhoods, landmarks, and people seemed to succeed solely on charm and on elbow-grease attention to detail (i.e., hand-drawing all those little bricks and roof tiles).

Westman’s lines were loose, her characters’ heads were large and often goofy, and her compositions were often raucously crowded, with cluttering, often comic, popping signage every which way. This additionally played to the fact that I was learning to love graphic design. The editorial remarks Westman snuck onto street signs (like the parking restrictions that simply bark, No, no, no!) cracked me up, and at first I almost could not believe her audacity to take this kind of poetic license with real places.

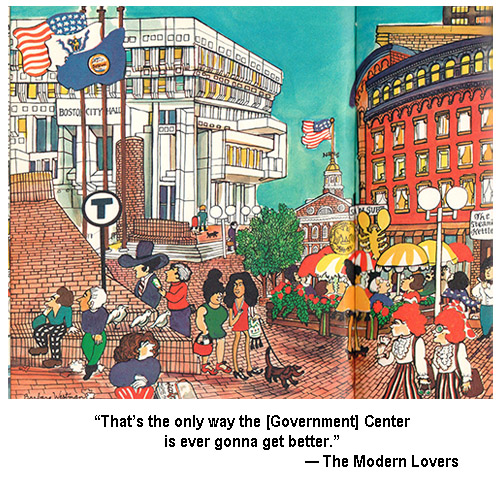

Westman’s drawings also became sort of fetish objects for me simply because they served as easily-accessed representations of other fetish objects of mine: big Boston buildings. I wanted in to the city for as long as I can remember. And not because I felt (or feel) myself too sophisticated for suburban life. Boston seemed the place where the action was, and where I wanted to be, because it was such a happening, target-rich environment of exciting school field trip-type places like the aquarium and the Museum of Science and the U.S.S. Constitution and that really cool kids’ museum with the giant milk bottle snack bar outside. I’m not lying, either, when I say that it was the offbeat and somehow classier toys and souvenirs in the gift shops of those kid-friendly institutions that really got me going.

Westman’s drawings also became sort of fetish objects for me simply because they served as easily-accessed representations of other fetish objects of mine: big Boston buildings. I wanted in to the city for as long as I can remember. And not because I felt (or feel) myself too sophisticated for suburban life. Boston seemed the place where the action was, and where I wanted to be, because it was such a happening, target-rich environment of exciting school field trip-type places like the aquarium and the Museum of Science and the U.S.S. Constitution and that really cool kids’ museum with the giant milk bottle snack bar outside. I’m not lying, either, when I say that it was the offbeat and somehow classier toys and souvenirs in the gift shops of those kid-friendly institutions that really got me going.

Lucky for me, whose juvenile and adolescent sensitivity and proneness to anxiety could hardly have handled it, I don’t believe I was ever technically unclear about my sexual preferences. I always loved girls. But I was never butch, not by any stretch of the imagination. I identified with the “opposite” gender more than my own. At family get-togethers the men would listlessly gravitate to my grandfather’s den to watch football amid bursts of smoke from the cheap tobacco in the typically shirtless old man’s pipe. But I was the type who wanted to sit in the kitchen with my warm and unprepossessing WASP grandmother and her dusky and broad-faced  Italian hairdresser sisters-in-law up from Rhode Island and listen to the gossip. I got something—I’m still at pains to describe just what—from what at the time seemed to be the feminine worldview. I was even drawn to the newspaper comic strip Cathy because I found her defining character traits of fussiness and indecision both winning and cute. (My father, however, once employed a rare heavy hand in discouraging me from buying a softcover Cathy omnibus at a certain point in my preteen years. He was usually tolerant of my odder choices, although I would tend to attribute this more to the low expectations I had inspired in him than for enlightened progressive parenting).

Italian hairdresser sisters-in-law up from Rhode Island and listen to the gossip. I got something—I’m still at pains to describe just what—from what at the time seemed to be the feminine worldview. I was even drawn to the newspaper comic strip Cathy because I found her defining character traits of fussiness and indecision both winning and cute. (My father, however, once employed a rare heavy hand in discouraging me from buying a softcover Cathy omnibus at a certain point in my preteen years. He was usually tolerant of my odder choices, although I would tend to attribute this more to the low expectations I had inspired in him than for enlightened progressive parenting).

Barbara Westman’s drawings were also highly feminine. And I responded eagerly to this. It would be the same years later when I finally got to know the cartooning of Roz Chast and Lynda Barry, to which I pledge sentimental attachment for life.

Later, it was a thrill to learn that Westman had devoted an entire book to Cambridge, The Bean and the Scene. Cambridge had presently become the emotional equal of Boston in my estimation, especially once I discovered comics and, in turn, The Million Year Picnic, the seminal comic book store on Mt. Auburn Street. Again, it would take many more years for me to acquire the cultural knowledge and personal experience to get some more proper sense of Boston’s rightful place in the universe. But in those days Boston and Cambridge struck me legitimately as the crossroads of the world. Far more so than New York City, in fact, which to my 1970s and early 1980s self had been irretrievably colored by a reputation for filthiness, coarseness, unjustifiable swagger (the Red Sox vs. Yankees rivalry even affected a decided non-sports fan like me),crime, and violence.

Later, it was a thrill to learn that Westman had devoted an entire book to Cambridge, The Bean and the Scene. Cambridge had presently become the emotional equal of Boston in my estimation, especially once I discovered comics and, in turn, The Million Year Picnic, the seminal comic book store on Mt. Auburn Street. Again, it would take many more years for me to acquire the cultural knowledge and personal experience to get some more proper sense of Boston’s rightful place in the universe. But in those days Boston and Cambridge struck me legitimately as the crossroads of the world. Far more so than New York City, in fact, which to my 1970s and early 1980s self had been irretrievably colored by a reputation for filthiness, coarseness, unjustifiable swagger (the Red Sox vs. Yankees rivalry even affected a decided non-sports fan like me),crime, and violence.

A reviewer from the Harvard Daily Crimson, however, was not so thrilled with Westman’s characterization of the community. In the only real piece of criticism I have been able to find on her work, The Bean and the Scene was excoriated. And, I find myself now having to add, not entirely unfairly.

I must confess my online research skills have been incompetent to establish whether or not Ms. Westman is still with us. For someone who has a number of New Yorker covers to her name and multiple pieces in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, it’s a bit surprising Westman boasts no Wikipedia page, no passing references in even the Boston Globe archives, nor nearly any other mainstream newspaper or magazine I can find—to say nothing of a personal website or fan page.

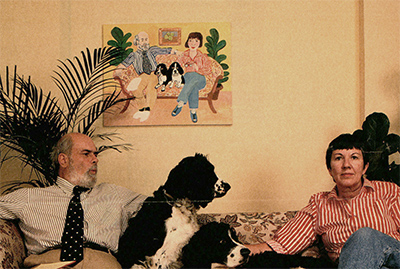

I do know that she married the late philosopher and art critic Arthur C. Danto, noted for his belief that art history was “over.” And, since her husband was based at Columbia, it seems Westman shifted her life and focus to New York City. She and Danto were photographed in their living room for the New York Times Magazine posing under a self-portrait clearly rendered by Westman. They look every inch the picture of that sort of soaringly accomplished yet eccentric Manhattan couple, so blending the highbrow with the bohemian that you can imagine them maintaining it vulgar to be written about too much. Or, heaven help us, have a social media presence.

I do know that she married the late philosopher and art critic Arthur C. Danto, noted for his belief that art history was “over.” And, since her husband was based at Columbia, it seems Westman shifted her life and focus to New York City. She and Danto were photographed in their living room for the New York Times Magazine posing under a self-portrait clearly rendered by Westman. They look every inch the picture of that sort of soaringly accomplished yet eccentric Manhattan couple, so blending the highbrow with the bohemian that you can imagine them maintaining it vulgar to be written about too much. Or, heaven help us, have a social media presence.

Barbara Westman, if you’re out there, I hope you find this as a long overdue memorial.

You are to Boston what Bemelmans was to Paris. And I for one only wish there was more.