It is an enormous joy, an honor really, to have the privilege of graduating my first published work of comic book fiction, Epochalypse, from abstract “hey, wouldn’t that make a cool idea for a sci-fi story?” concept to something physically and electronically available for the mass public to peruse.

It is an enormous joy, an honor really, to have the privilege of graduating my first published work of comic book fiction, Epochalypse, from abstract “hey, wouldn’t that make a cool idea for a sci-fi story?” concept to something physically and electronically available for the mass public to peruse.

If you have beaten a path to this paragraph, I can only hope it’s because you or someone you know has found Epochalypse interesting. I believe it to rate as a novelty, at least, for a comic book to be set in a dark, post-cataclysmic vision of Western Massachusetts and the so-called Capital District of New York State. (That being said, between A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and Rip Van Winkle, the soils of New England and the Hudson Valley are no stranger to the time travel narrative).

And what of this time travel narrative? You know — as a genre? It is surely one picked-over and denuded stretch of salad bar.

Time travel stories reach back to works as ancient as several hundred years before they put us on notice to change our calendars from B.C. to A.D. In those venerable examples, dreams, magic, or divine influence made chronological dislocation possible. But the time travel genre really began nudging its way towards the mainstream during the late Victorian Age. Groundbreaking work in theoretical physics was being done then. And this is to say nothing of the flood of new inventions like electricity, automobiles, and motion pictures that were goosing up people’s imaginations.

In short order, science and technology replaced fairies and gods as the engine of time travel.

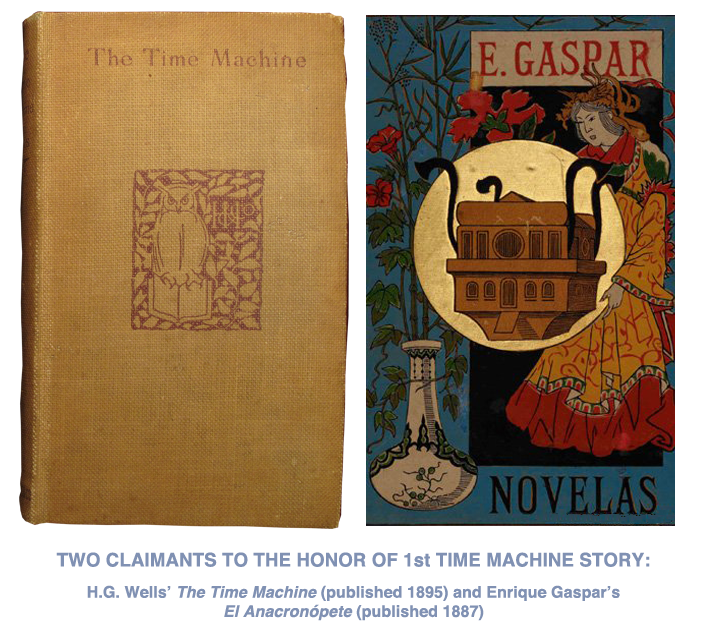

The go-to claimant of inventing the “time machine” is of course H.G. Wells. Wells, in 1888, penned a short story conceptual precursor to his famous 1895 novel The Time Machine. But in fact an ambitious playwright — one who had found a way to support his mania for fiction by, oh nothing, just becoming his country’s ambassador to China — beat Wells to the time machine punch. This was with the novel El Anacronópete by the reportedly flamboyant and charismatic Spaniard Enrique Gaspar. El Anacronópete was written in 1881 and published in 1887.

Nevertheless. In the genre of time travel, Epochalypse — I would offer — takes an unconventional zag where other stories of this well-worn tradition zig.

In Epochalypse, an inexplicable force has caused some 600 years of history — from the 1600s to the late 2100s — to violently collapse into a single new timeline.

Instead of one or a few individuals traveling in time and having some control over where they end up, here something makes everyone spontaneously time travel. They all get sucked into the time-spectrum’s midpoint: the year 1951.

What is left for those few who survive the journey is a ravaged world where people from the past, present, and future all find themselves living side by side. Cultures, technologies, ideas, and ideologies never meant to coexist suddenly find themselves overlapping. No one knows why or how this happened. (Or how to prevent it from happening again). And most critically of all, no one seems to have made any real progress with setting history right again — and liberating all these anachronistic refugees back to their “home times.”

In other words, Epochalypse is a time travel story where all the time travel has played out well before Page 1. And since the story’s clock-crunch just about dealt a death blow to civilization, you might at times be tempted to call this “science fiction by candlelight.”

You won’t find a Murderer’s Row of big names here. Hiawatha, Aaron Burr, and JFK are not going to team up with an axe-wielding Lizzie Borden to go out and hunt bad guys.

No. The main characters in Epochalypse are ordinary individuals plucked out of a broad swath of real (for those from the past) and notional (for those from “the future”) American history.

(That being said, what qualifies as “the future” is something of a moving target in this story. But the people who have come to be in positions of authority in the Epochalypse world, as you may discover, have significantly and controversially drawn that line at 1952 and later).

Our hero is Johannes Van Der Honing, violently dashed as a young boy from the year 1645. Johannes is an driven yet empathetic enforcer of the startlingly repressive laws of the “The New Now.”

Johannes and his colleagues are tasked with untangling the space-time knot. They vie to reverse the disaster that has thrown superstitious New World colonists and everyone in between with those from a hard-to-get-a-handle-on future — where humans prove to have transcended almost every physical and psychological limitation. Except maybe their own capacity for self-delusion and self-destruction.

(I promise you’ll start to get some intriguing glimpses of this vision of the future — and the extent to which just how alien the “present” has truly become — beginning in Issue #3).

The heroes of Epochalypse are trying to save history. But this is neither an easy task nor a forgiving one. Along the way, they will find themselves facing some tough and torturous questions about whether or not history as we know it is worth saving in the first place. Some may conclude — to the dismay of their closest allies and their own personal codes of honor — that if fate has handed the world a colossal reset button, even the billions of dead might be better off just starting from scratch.

Look, there are ingeniously compelling stories being told all around us right now. Maybe more than ever. It’s not easy launching any series from scratch, especially with a writer who’s a nonfiction midlister at best. Epochalypse could easily do no more than sleepwalk into the always-welcoming, “open 24/7 to serve you” arms of obscurity.

But all the same, aspiring creators out there should take heart from my example. The idea for Epochalypse first popped into my head half my life ago. (And it is with no great zeal that I confess that’s double-digit-decades at this point). This happened on a drive through the same part of the country where the narrative is set. I began working on the story — developing it in earnest — at least by 2001. Then, for many years, it was titled Synchroni-City. And it briefly took the shape of a Twilight Zone-y short film script read aloud to a long disbanded writer’s group that met every month in a cheap rental apartment in Glendale, California. Epochalypse has gone through many permutations and (this is the part where I roll off with an irretrievable cliché that is at the same time an undeniable truth) withstood many rejections. I’ve pitched it by letter, phone call, meeting, and email. I’ve haunted portfolio review lines at comics conventions hoping to meet artists who might bring it to life. I’ve bum-rushed editors at those same shows who clearly did not want to be bum-rushed. I’ve written and rewritten and rewritten character bibles, loglines, and plot synopses before ever getting far enough along for readers to actually have something they can buy.

This is all to point out that if you have been toiling for years in humbling circumstances on a story idea or project that is “your baby,” keep it up. This thing is a marathon. Not a sprint.

The fact that Epochalypse ever existed to maybe pique your interest at all can be attributed to a handful of true worthies. They must now be given their due. The legendary (pun intended) comics editor Bob Schreck saw potential here and rolled the dice even when people he trusted and respected had not. Thomas Tull asked poignant, hyperinformed, searching questions about this concept and story — and then had the good graces not only to accept the answers I gave him, but also demonstrate a willingness to let this mother run up the flagpole to see if it’ll fly. I would venture that Greg Tumbarello had Bob’s back as Mr. Tull let him take it from there — Greg certainly had mine. Just as David Sadove, Robert Napton, and entertainment attorney Wendy Heller did.

Shane Davis did a bang-up job giving Epochalypse its form and establishing the people, places, and energy of this story. Thank you, Shane. And my longtime collaborator Aaron McConnell, who preceded Shane in some early, unpublished, proof-of-concept iterations of Epochalypse, was a tireless advocate for it. Without him this little introduction might never have had cause to be written. My wife Annie Oelschlager might not be enough of a nerd (at least not this flavor of nerd) to get the appeal. But she saw the appeal in my sticking it out long enough to make it happen.

Let me be the first to invite you to check out Epochalypse, debuting November 19th from Legendary Comics. It is available in stores and on Comixology.

Your friends and fellow fans deservedly trust your opinion way way more than mine. So if you like what you see, I’d be thrilled if you would spread the word.