When the delegates to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention met for the debates out of which the U.S. Constitution emerged, they didn’t just bring with them their grievances with monarchy and with history’s variously compromised iterations of democracy and republicanism. Many of those we hail as Founding Fathers were personally bitter about far more recent political arrangements. Even relatively just and enlightened ones.

Benjamin Franklin was among those who identified themselves as eyewitnesses to abuses of power and self-dealing within the Colonial Era governments of which Americans tended to be so proud.

Franklin wanted to see good government take root in the states. Of course he desired that America’s leaders be virtuous and disinterested. And Franklin would express particularly strong opinions about the individual who would occupy the office of the president.

The elderly polymath felt that, through his own experience with official corruption, he had earned the right to stand up, speak out, and ensure that set down in the Constitution would be practicable measures to guard against presidents who would use the office for personal gain. “I have lived long enough to intrude myself on posterity,” Franklin jocularly asserted.

It was June 4, 1787. Franklin proceeded to dust off a telling example of a deeply extortionate executive magistrate with whom he had repeatedly locked horns during the French and Indian War.

General George Washington, presiding over the convention, had been personally entwined in the grander aspects of that event. The 1754–1763 conflict had made Washington both an international failure and an international hero. What’s more, Washington’s trans-Allegheny soldiering experience had also stoked the fires of his lifelong mania for further enriching himself by accumulating land.

Benjamin Franklin’s involvement in the French and Indian War had ranged from establishing postal routes and roads between Philadelphia and the British expeditionary force’s combat outposts, and helping the army secure horses, wagons, drivers, and other supplies. But for Franklin, one obstacle proved to be as obdurate as the unthinkably dense old-growth forest that stood between the Anglo-American cannons and the distant prize of French Fort Duquesne. That obstacle was Pennsylvania Governor Robert Hunter Morris. (This is a man not to be confused with “financier of the American Revolution” Robert Morris Jr.).

“No good law whatever could be passed without a private bargain with [Morris],” Franklin lambasted the colonial governor, whom by this juncture Franklin had long outlived. “An increase of his salary, or some donation, was always made a condition; till at last it became the regular practice, to have orders in his favor on the Treasury, presented along with the bills to be signed, so that he might actually receive the former before he should sign the latter.”

Franklin’s cri de coeur about the dangers of politicians who would line their own pockets was follow-up from his two-days-earlier petition that the U.S. president should receive no compensation at all.

It emerged as one of many of the convention’s compromises that the president would receive a presumably handsome yet not princely salary — one to be set by Congress. After all, without compensation of any kind, a president might become especially tempted to earn his daily bread through acts of graft. James Madison declared a presidential salary to be necessary to move a president “out of the reach of foreign corruption.”

The material perks and advantages from which a president might further benefit, either by overt act or by being a passive and involuntary recipient, were hemmed in even further by the framers of the Constitution. Twice in the Constitution they codified provisions to counteract any attempt, by any interested government party, to enlarge the president’s compensation. This was achieved through Art. II, Sec. 1, Par. 7’s “Domestic Emoluments Clause” as well as Art. I, Sec. 9, Par. 8 “Foreign Emoluments Clause.”

The Domestic Emoluments Clause reads as follows:

He [the president] shall not receive within that Period [his four-year term in office] any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.

What this means is that aside from his congressionally-mandated and -set salary, the president is disbarred from receiving any other form of direct or indirect income, benefit, or advantage from any part of the federal government (such as the Export-Import Bank or the U.S. Coast Guard) as well as from any other domestic government. This includes states, cities, counties, and all of their individual instrumentalities, such as a police departments or state universities.

Through these enactments the framers sought to erect a sort of firewall between the president, the states, and all other governmental appendages. Franklin’s Robert Hunter Morris example had been raised as an object lesson in the importance of executive function efficiency. Franklin had been complaining that government would function too slowly, and would inadequately address the demands of the moment, if the president had to be constantly spurred by money and favors into performing his duties.

The Domestic Emoluments Clause also is intended to guard against presidential favoritism. For surely if one particular state or governmental agency were to shower the president with gratuities or opportunities for enrichment, that state or agency would stand to reap tremendous patronage and consideration in return. Within a framework of coequal branches of government, within a union of states who are equals in many respects, such displays of presidential partiality would assuredly fail to secure domestic tranquility.

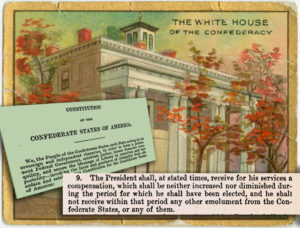

It is not just the people of the Revolutionary Era who saw fit to include a Domestic Emoluments Clause in their Constitution. Three-quarters of a century later, the constitution of the Confederate States of America essentially cut and paste the same language into their own Article II.

Nevertheless, it suits many to write off the emoluments clauses as obscure, little-noted, and historically unenforced. They place them among the passages of the Constitution that deserve to be consigned to the “dustbin of history.”

Indeed, it is unusual for the clauses to ever surface in either law articles or popular discourse when government is perceived to be functioning well (or at least perceived to be functioning at an acceptably ordinary standard).

The scant knowledge of and attention paid to the emoluments clauses is not at all surprising. In fact, it can be taken as a sign that national governance is generally healthy; that the Constitution is working.

Think of it this way. Any given person under typical circumstances is unlikely to be giving inordinate heed to air chambers in home plumbing systems, the relays and modules that control automobile headlights, or the condition and function of the pineal gland. That is, we usually remain blissfully oblivious to these unless and until something goes wrong with them. These items exist in the world, operating in the background. The fact that we do not acquaint ourselves with them until some development demands it in no way diminishes their essential reality.

In like fashion are the Constitution’s admonition that states are not to coin their own money; that only the federal government can issue letters of marque and reprisal; and that no attainder of treason must ever work “corruption of blood” or forfeiture.

It’s not that these passages of the Constitution don’t or shouldn’t have force of law. They are not the equivalent of folksily amusing, unrepealed old state ordinances like those enjoining New Jerseyans from spitting in public, or demanding that citizens of Georgia to bring their muskets to church.

These “arcane” clauses of the Constitution have instead over time been so fully and seamlessly absorbed into mainstream American law that they customarily go unnoticed. If Hawaii or South Dakota started issuing its own currency, you can believe the matching “esoteric” Constitutional provision banning the same would spring into rigorous enforcement and seize national headlines.

So it is that tense times and divisive political figures seem to be conducive to emoluments clauses controversies. Between long valleys of remission, they form the peaks that produce high emoluments clauses awareness.

For example, President Richard Nixon was a walking seedbed of emoluments clauses issues.

As the Watergate scandal intensified, Domestic Emoluments Clause scrutiny was brought to bear on some $17 million from the U.S. Treasury that had been spent improving Nixon’s private residences in San Clemente, CA, and Key Biscayne, FL. Violation of the Domestic Emoluments Clause was included among the articles of impeachment that were being prepared by, among others, House Judiciary Committee member Joshua Eilberg in 1974. (Nixon, of course, resigned before an impeachment trial could take place).

In 1982, the pension Ronald Reagan had been receiving from his tenure as governor of the state of California was flagged by critics as a potential violation of the provision.

Arguably, however, no chief executive can be credited with vaunting the emoluments clauses to heights of public awareness like Donald J. Trump.

Trump, through his interests in a moderately-sized chain of hotels, commercial buildings, golf resorts, and the like, has drawn an unprecedented amount of proverbial fire. On one flank he has been raked by accusations that he is violating of Foreign Emoluments Clause. On the other flank, it’s the Domestic Emoluments Clause.

As to the latter, the Secret Service has expended considerable dollars renting space and golf carts, paid for in the course of agents’ duties during the president’s many stays at his properties like Mar-a-Lago and his resort in Bedminster, New Jersey. (While Vice President, Joe Biden also received rent payments from the Secret Service when agents rented space at his private residence in Delaware). When Maine Governor Paul LePage made a trip to the nation’s capital on official business, he and his entourage booked an expensive suite of rooms and ran up significant parking and room service bills at the president’s Trump International D.C. Hotel.

The Trump Organization, by dint of its operation of this same hotel, has additionally received nearly $1 million in tax concessions from the District of Columbia. The lease of the hotel building itself has been alleged to be a Domestic Emoluments Clauses violation. That is because the Old Post Office Building, which was renovated to house the hotel, is federal property managed by the General Services Administration.

If indeed President Trump is violating both the Foreign and Domestic Emoluments Clauses with his private business interests, neither the executive branch nor the partisan majority in the legislative branch of the federal government has taken any action to rectify offenses to the Constitution. The president has faced multiple lawsuits on this controversy from parties inside and outside government.

To date, no lawsuit has yet ended with results calling the president to account. Currently District of Columbia, et al. v. Trump, is moving forward after the plaintiffs, the State of Maryland and the District of Columbia, were found to have standing and Judge Peter J. Messitte opined that Trump’s actions constituted “plausible” violations of both emoluments clauses.

Some legal scholars have forwarded arguments that favor the administration and find no legal fault with Trump’s business activities. Possibly the scholar in this vein whose work has been most widely successful in making its way out of law journals, blogs, and amici curiae to the court and into mainstream publications like the New York Times and The Washington Post is Seth Barrett Tillman. Tillman is a faculty member in the College of Law at Maynooth University in Ireland, and an American national.

Tillman’s thesis is comprehensive, coherent, and many-layered. Space will not be reserved here to consider it in its entirety. Perhaps the most prominent feature of the thesis is the argument that the framers of the Constitution never intended the Foreign Emoluments Clause to apply to or “reach” the president.

The judge in District of Columbia, et al. v. Trump devoted many pages of his opinion to parsing and ultimately discrediting the myriad elements of Tillman’s scholarship.

But the Honorable Judge Messitte did not delve in great detail into one particular facet of Professor Tillman’s argument — at least not to Professor Tillman’s satisfaction.

This article will go on to offer the deep analysis that seems to have been beyond the scope of the July 25, 2018, legal opinion.

Throughout this nearly two year-long odyssey of the suspiciously muscular promotion of Professor Tillman’s ideas in this area, there has perhaps been no argument he has more consistently attempted to employ as a buttress than the allegation that George Washington himself “brazenly” violated Article II’s Domestic Emoluments Clause—and did so in such a way as to mitigate or indemnify President Trump’s own conduct in regards to the provision.

The source of Tillman’s allegations lies in an episode from 1793.

Early in his second presidential term, while the federal government still resided in Philadelphia, Washington journeyed to the embryonic “federal city” that would become what we know today as Washington, D.C. Foremost on the president’s schedule was taking part in a Freemason parade and accompanying ceremony that would mark the laying of the cornerstone for the U.S. Capitol.

The nation’s permanent seat of government was then little more than narrow right-of-ways cut through virgin forest and a few half-cleared lots bedeviled by stubborn tree stumps. Without even a bridge by which the procession could access Jenkins Hill (later Capitol Hill), the Father of His Country was obliged to traverse Goose Creek via a fallen log, or else jump from rock to rock after detouring upstream from the parade route.

The parade and ceremony had been largely ginned up to attract investor interest in the planned metropolis. For investor interest was sorely lacking.

The making of Washington D.C. was, in fact, much more a grand real estate scheme than it was a federal government project. And early on it widely seemed that the only thing “grand” about the scheme’s realization was how ruinous a failure it stood to be.

In a telling instance in October, 1791, one of Washington’s appointed commissioners — the men directed to oversee the raising of the city — warned the president that land sales so far had been lackluster. He blamed bad weather, and reported, “We have thought proper as the business seemed to flagg [sic] a little today, to discontinue the sale.

At the time the United States planned to erect no more than two government buildings in the land that Maryland and Virginia had agreed to cede to the infant U.S. government. The Capitol and the “President’s House” were the sum total of what Congress had committed to. Even then, the legislative body had not appropriated a single cent for the construction of these edifices.

Where was the money to come from? Answer: from dividing much of the set-aside ten square mile federal district into lots, and selling them off to private speculators.

Washington announced this in his opening message to the 2nd U.S. Congress:

A City has also been laid out agreeably to a plan which will be placed before Congress: And as there is a prospect, favored by the rate of sales which have already taken place, of ample funds for carrying on the necessary public buildings, there is every expectation of their due progress.

If a viable city fit to host the chief executive, the supreme court, and the legislative representatives of the people was in the offing at all — not just the Capitol and the President’s House, but also taverns, churches, liveries, boardinghouses, residences, mechanics’ workshops, and so on — it was going to have to come about by private enterprise. But despite Washington’s optimism about “ample funds,” private enterprise was making no show of rising to the occasion.

The president and indeed the Union itself had much at stake in this. George Washington, already a real estate grandee in northern Virginia, was famously afflicted with “Potomac Fever.” He had extensive private business interests in the immediate region, and the federal city’s existence would impinge sharply upon Washington’s lifelong dream of remaking the river into a bustling trade corridor to open the Ohio Valley.

Personal, political, and P.R. disaster loomed if the nascent capital failed to make headway. Congress might get cold feet and decide to repeal the 1790 Residence Act, the directive that the government must take up its new headquarters by December 1, 1800. To abandon this plan would be to keep all the business, energy, and influence that the federal government generated where it currently could be found, in Philadelphia. And Philadelphia would be only too glad to see this play out.

If the construction of Washington, D.C., fizzled out, it wouldn’t just undermine Washington’s landholding empire. It would also amount to a major embarrassment on the world stage to the untested American republic. It would offer proof that the people of the U.S., as British economist Josiah Tucker predicted in 1781, would have “no center of union,” “no common interest,” and were only destined to be a “disunited people.”

Indeed, there was at least one selflessly patriotic criterion implicit in Washington’s desire to refashion the Potomac into an inland-bound superhighway. Washington was vexed that if the frontier remained too inaccessible to migration and trade, it would enfeeble westerners’ attachment to the United States as a political entity. The pioneers might instead flock to the Spanish (in control of the Mississippi and the Far West) or the British (who still possessed Canada and who still loitered in their own forts in the northwest). And they would take not just their fealty but their lands with them.

Investment in the federal city needed a shot in the arm. So it had been agreed that to capitalize on the grandeur of the Freemason parade and Washington’s visit, the September, 1793 occasion would culminate in three days of the auctioning of city lots.

The September 18, 1793 auction Washington attended turned out to be yet another worrisome underperformer.

“There were few raised hands, few shouted voices,” writes historian James Flexner (whom Tillman also cites extensively in his amici curiae).

At last, a likely highly embarrassed Washington broke the silence. Motivated, one can only deduce, by the desires to service his Potomac Fever, preserve the tenets of the 1790 Residence Act, and spare his administration, himself, and the assembled guests the mortification of witnessing the day’s pomp devolve into farce, Washington bought four lots — four parcels of empty land now near Buzzard Point Park, by 1st Ave SW and V Street SW.

This is the act that constitutes Tillman’s ringing alarm bells of potential Domestic Emoluments Clause offense.

“According to the Plaintiffs’ definition of ‘emolument,’ President Washington received something of value from the federal government, beyond his salary — that is, he received the land,” writes Tillman.

He goes on thusly:

If Judge Messitte’s [of District of Columbia et al. vs. Trump] interpretation of the Domestic Emoluments Clause and its “emoluments”-language were correct, then Washington violated the clause, and his three commissioners conspired to help him do so in full light of day.

The choice before us is a simple one: either: (1) President Washington and his three commissioners (including a Supreme Court Justice) were right, and Judge Messitte is wrong; or (2) Judge Messitte is correct, and President Washington and his three commissioners were wrong.

There is a third choice that Tillman did not perform the necessary historical research to anticipate. There are many reasons to believe that Washington was not genuinely doing business with the federal government in this instance.

Anyone defaulting to a presentistic sense of how the federal government operates would probably assume that the land on which the federal city was to be built had been purchased outright by the federal government through an act of Congress. Or, alternatively, that the government had acquired the property through eminent domain or a grant of title by a state (in this case, Maryland).

But that was not how things worked in 1791–1793.

It must be remembered that the United States government was brand new and essentially untested. The holdings of the U.S. Treasury were diminutive. The country’s debt from years of war with Great Britain still hamstrung it and severely circumscribed what priorities it could act upon. The government held precious little taxing power or methods of raising funds. Neither could it finance a grand project. Throughout the previous post-Revolutionary War decade, America’s credit in foreign capital markets had been spotty at best.

Moreover, 1792 had been visited by a drastic financial panic brought on by rabid bank speculation. This engendered widespread mistrust of the federal government and financial schemes in general. America’s citizens might have been called guardedly hopeful about their new government, but they were wary in the extreme that it might wield too much power. The people were not prepared to stomach the loosening of purse strings for so massive a federal project as the erection of castles in the Maryland woods.

Although the legislatures of Maryland and Virginia had approved ceding some of their territory to the federal government for use as a national capital, this cession was not to conveyance of property but instead a transfer of sovereignty and legal jurisdiction over the land. (The actual site of the city had not at that point been determined. Although the location was, by law, to be on the Potomac River, the 1790 Residence Act enabled Washington to personally to establish the federal city as far inland and northeast as Williamsport, Maryland. Near Hagerstown, this is about a 90 minute drive from Capitol Hill).

The deeds to, and ownership of, Washington D.C.’s land itself remained in private hands.

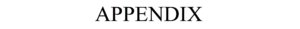

There were various parcels belonging mostly to residents of the towns of Georgetown, Maryland, and Arlington, Virginia. (See appendix, Map of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia, showing the lines of the various properties at the division with the original proprietors in 1792, https://www.loc.gov/item/87694265/).

George Washington himself, once he had set his mind to locating the city upon the Eastern Branch of the Potomac, traveled to the Georgetown and Arlington in person to try to get the consent of the local landowners, or “proprietors,” and negotiate some mutually beneficial agreement for the public to acquire the land.

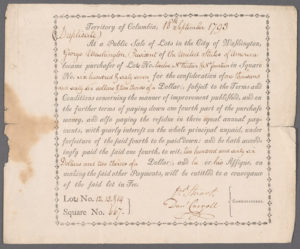

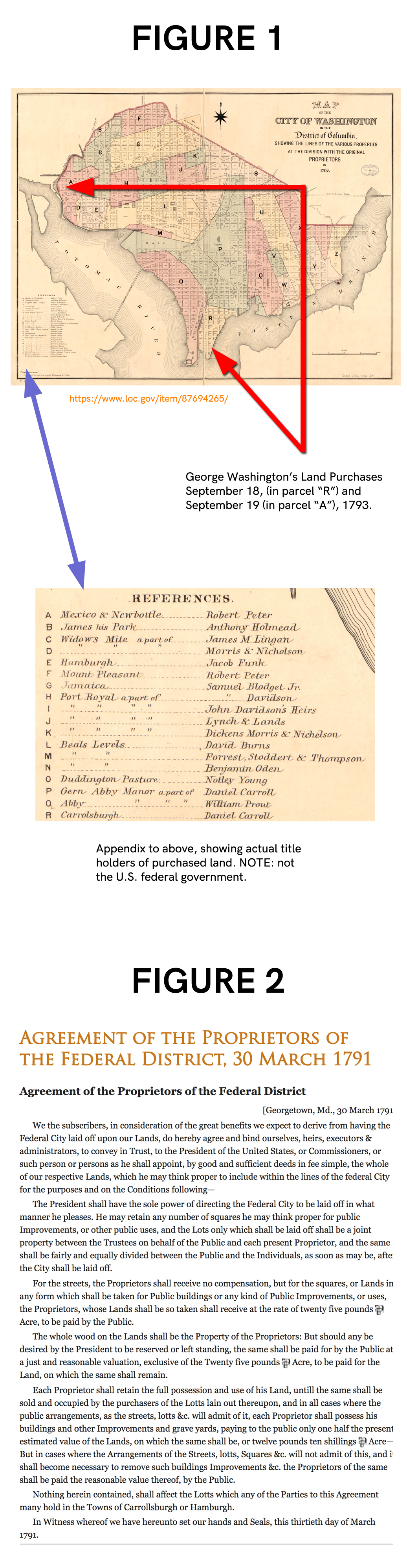

Eventually the proprietors consented to “convey in Trust” their lands to Washington and his commissioners. Not a penny would change hands at this point. The entire consolidated district would then be laid out into lots.

Once streets, squares, and other public improvement sites were placed, the remaining lots would be divided in half. The proprietors were to retain every other lot, maintaining their private ownership in the bargain. The remaining lots were to be granted to the federal government. The federal government then would sell these. The revenue generated would be used to finance the construction of the Capitol, the President’s House, roads and bridges, etc.

Anyone purchasing lots on September 18, 1793, then, was not purchasing them from the federal government. They were instead purchasing them from the legal trust Washington and the proprietors had created by virtue of the “Agreement of the Proprietors of the Federal District, March 30, 1791.” (See appendix).

Cutting crucially against Professor Tillman’s position that Washington received land from the federal government, that same agreement contains a clause that reads as follows:

“Nothing herein contained, shall affect the Lotts which any of the Parties to this Agreement many hold in the Towns of Carrollsburgh or Hamburgh.”

Carrollsburgh and Hamburgh, both of which were hamlet-sized, port outposts of Arlington, Virginia, and Georgetown, Maryland, were relatively distant from both the site of the Capitol and the site of the President’s House.

Since the federal government apparently held no immediate plans for these areas, it evidently made sense from the outset to exempt them from the Trust.

We know that the lots that Washington purchased the day of the Freemason parade were situated in Carrollsburgh. The purchased land was the property of Daniel Carroll, a large Montgomery County, Maryland, landowner. Carroll was also a signatory of the 1791 Proprietors’ Agreement. (Carroll was also a former member of the House of Representatives, and in 1793 was currently serving as one of Washington’s own federal city commissioners).

We also know that there existed a great deal of competition and jealousy between land proprietors on the north side of the district and the south side of the district. Both groups, with an eye towards recouping the loss of their land, were anxious that their own property be improved and developed.

So Washington, as auctions continued on the second day of the affair, undertook a maneuver calculated to cast himself in an impartial light. He purchased another four lots in Hamburgh — standing,in the present day, near a parking area for Rock Creek Park just southeast of Georgetown.

The following words of Washington’s, written six months later, attest to this:

In September last, after having purchased four lots in Carrollsburgh (the doing of which was more the result of incident than premeditation); and being unwilling from that circumstance, it should be believed that I had a greater prediliction to the southern, than I had to the Northern part of the city, I proposed next day (the sale being continued) to buy a like number of lots in Hamburgh, and accordingly designated the spot.

In light of the above clause which exempts Carrollsburgh and Hamburgh lots from the agreement, this indicates that when Washington made his purchases he was not even entering into a business transaction with the Trust.

It may very well be that the was dealing on a personal basis with Daniel Carroll for the Carrollsburgh lots, and Robert Peter for the Hamburgh lots. (There is some slight confusion here, for though Washington reports buying lots in Hamburgh, the Map of the City of Washington labels these lots in a very nearby, adjacent parcel called “Mexico & Newbottle.” This parcel, however, is situated close enough to that which is designated “Hamburgh” to reasonably that conclude common period usage might lump them together.)

Indeed, had it been federal government holding title to the land, and had it been the federal government receiving the benefit of the lot sales, instead of local private landowners with commercial interests, why would Washington have acted with such deference? Why would he have undertaken such pains to treat both groups of private proprietors equally?

Between the existence of the Trust on the one hand, and the clear evidence that Washington’s specific lots were purchased from private citizens in arrangements that circumnavigated the Trust on the other, we can only conclude that Washington’s transactions in no way violated the Domestic Emoluments Clause.

President George Washington did not receive something of value from the federal government beyond his salary, because the land Washington purchased was not the federal government’s to sell or give him. There is no Washington “emolument.”

Even if Washington had provably been transacting business with the federal government in this case, the land the president acquired would arguably not qualify as an offense to the Domestic Emoluments Clause.

Recall the contingency that any given item of value, to fall under the umbrella of the emoluments clauses, must arise in the constitutional context of influencing or attempting to influence a public official.

Washington purchased these lots at a public auction — one that even Tillman allows was advertised six months before in a Philadelphia newspaper. This was not some sweetheart deal being slyly proffered to the executive magistrate alone. The man stood, as he wished to for propriety’s sake, on an even playing ground with every other potential bidder. “I had no desire at that time, nor have I any now, to stand on a different footing from every other purchaser,” Washington wrote in 1794.

No other persons present were bidding on Washington’s Carrolsburgh and Hamburgh lots. The lands were not deemed adequately desirable to find any claimants whatever. Events since 1791, ones that deeply concerned Washington, were adding up to the prospect that the federal city land might not be of any value at all.

So how, we must ask, could this 1793 public auction of dubiously valuable properties be construed as a domestic government tactic to exert influence on Washington? Such a supposition is absurd.

Let us furthermore apply the Alexander Hamilton test he put forward in The Federalist #73. Did Washington’s impulsive snatching up of some lots in order to save face and prevent his and his hosts’ public embarrassment “operate on his necessities” or “appeal to his avarice?”

Much the opposite, in fact. Facing the very real possibility that the federal city scheme would fail, Washington, out of personal and political pride, was agreeing to take on not an obvious asset but instead a potential hassle, humiliation, and fiscal burden.

In light of all this, any claim that Washington violated the Article II Domestic Emoluments Clause with these 1791 land transactions lacks merit.

Taken in conjunction with the lengths that other Constitutional scholars have gone to refute Professor Tillman’s thesis—arguments that informed the opinion of the Hon. Judge Messitte’s—this evidence that George Washington did not, in fact, disregard the letter or substance of the Domestic Emoluments Clause further casts in doubt the legitimacy of any legal analysis to date that mitigates President Trump’s infringements of the emoluments clauses.