I recently came across this article asserting that the names “Khaleesi” and “Katniss” — the former inspired by a major Game of Thrones character, the latter by the heroine of The Hunger Games — were wildly popular names for female babies in 2014. You might rant (and some have) that this is a deplorable statement about our current obsession with mass media. You might go on (and some have) to diagnose the phenomenon of naming children after fictional characters as something that could only happen in a superficial cultural moment like our own. And certainly not in those “girls were girls and men were men” days of the Calvin Coolidge Administration.

Well, think again.

In celebration of the release of Epochalypse #3 today, I am taking a moment here to throw the spotlight on our story’s love interest, Ramona Walden, who is introduced on the very first page of the latest issue. I chose the name for this character because, among other reasons, she is among those Epochalypse characters from 1951 who did not experience any chronological dislocation of their own (but instead had tens of thousands of persons from the past and future catapulted into their own time). And you can make a good case that “Ramona” was the “Khaleesi” and “Katniss” of its day.

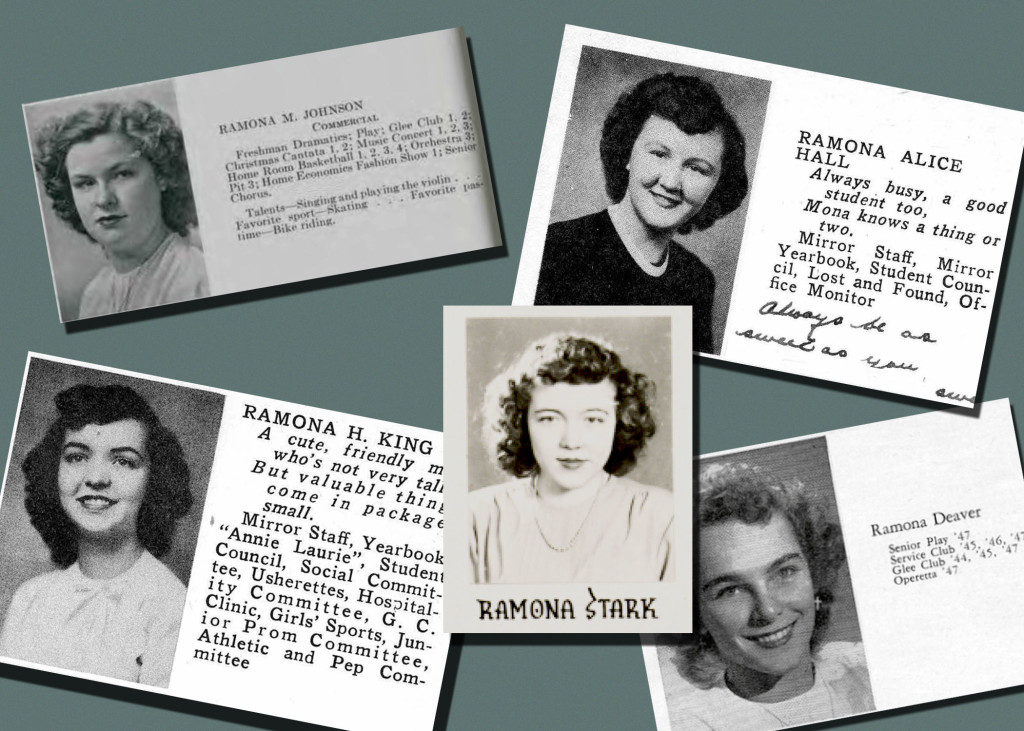

Ramona is a Spanish name. It’s the feminine form of Ramon. So why did American high schools in places as well removed from Iberian influence of any kind as Rutland, Vermont; Batavia, Illinois; and Madison, Wisconsin experience an enormous algae bloom of Ramonas in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s?

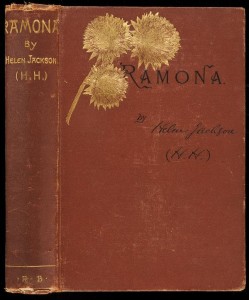

It’s because of a character in a book: Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson. Ramona was first published in 1884, and was a runaway bestseller. In addition, through a series of adaptations and hugely successful reprises — including several short and feature films from the Silent Era and one of the most technically-accomplished full-color “talkies” from 1936 — Ramona stayed culturally relevant for generations.

The writing and narrative style are dated for sure. But I still find Ramona kind of a fascinating work of literature because it’s set in the dim and distant past of where I have lived the past eighteen years or so. (My heart especially waxes romantic for the notion of weeks-long walks through an unbroken Southern California wilderness like those undertaken by the itinerant priest Father Salvierderra as he travels from mission to mission). Ramona also has a truly surprising and compelling negative point of view about post-White People California.

Ramona was supposed to do for Native Americans what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for the African American experience — namely, wake the racial mainstream of society up to an appalling legacy of injustice and inhumanity. The novel tells the story of a beautiful and sensitive “half-breed” young woman, part Scots, part Indian, who by somewhat tragic circumstances comes to live on a Southern California rancho shortly after the War with Mexico. “Greedy” Americans, their conquest of the Southwest now complete, are flooding into California. These Americans are portrayed as completely disrupting two ways of life: the placid, honorable, and devoutly Catholic society of landed Mexican gentry on the one hand, and on the other that of the Indian bands who maintain the most morally watertight claims on the land. Ramona falls in love with an Indian sheep-shearer Adonis who comes from a dying-out and impoverished tribe based in Temecula.

Ramona was supposed to do for Native Americans what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for the African American experience — namely, wake the racial mainstream of society up to an appalling legacy of injustice and inhumanity. The novel tells the story of a beautiful and sensitive “half-breed” young woman, part Scots, part Indian, who by somewhat tragic circumstances comes to live on a Southern California rancho shortly after the War with Mexico. “Greedy” Americans, their conquest of the Southwest now complete, are flooding into California. These Americans are portrayed as completely disrupting two ways of life: the placid, honorable, and devoutly Catholic society of landed Mexican gentry on the one hand, and on the other that of the Indian bands who maintain the most morally watertight claims on the land. Ramona falls in love with an Indian sheep-shearer Adonis who comes from a dying-out and impoverished tribe based in Temecula.

Despite their romance and good intentions both Ramona and her love, Alessandro, are eventually brought to ruin.

Jackson’s book was a smash success. It arguably didn’t do much for the people of the First Nations, who still wouldn’t even be legally considered American citizens until 1924. But it went a long way to romanticize the whole idea of the “California Mission” period. It also really got the ball rolling to transform sleepy Southern California into a high-octane tourist destination. In the no good deed goes unpunished department, Jackson’s effort to critique the modernization of California just redoubled the speed at which it has become a tangle of freeways and strip malls.

And, like I mentioned, the book produced a bumper crop of Ramonas.

Ramona, in Epochalypse #3, only dreams about headily miring herself with our hero, Johannes, in what their dystopian society would characterize as shocking moral turpitude. But Epochalypse #4 will show how far these two emotionally struggling and scrupulous young people both have actually gone to undermine their civilization’s values. As with everyone living in The New Now, they are forced on a daily basis to reconcile what their hearts want and what their duty is to the untold millions of history’s dead. There might be as stormy seas ahead for Ramona and Johannes as Ramona and Alessandro.

And lastly, no, I’m not trying to claim that I have bequeathed the comic book reading public as memorable a character as Katniss or Khaleesi. I’ll give it the old college try, though. Maybe I can at least go toe to to with Beverly Cleary.